I am a dynamicist. By this I mean that I try to understand and predict the dynamical evolution of a wide variety of astrophysical systems, such as binary black holes, star clusters, and galaxies. To do this I use the tools of theoretical physics (e.g. Hamiltonian mechanics, nonequilibrium statistical mechanics and kinetic theory), but I also employ numerical simulations and am involved with (and continually guided by) observational data.

My research so far can be categorized into four broad areas: (i) the dynamics of disk galaxies, (ii) the kinetic theory of stellar systems and plasmas, (iii) compact object mergers; (iv) wide stellar binaries.

Dynamics of Disk Galaxies

Disk galaxies occupy an especially prominent place in modern astrophysics, as the setting for many of our most profound puzzles. The nature of dark matter is still a mystery half a century after the discovery of flat rotation curves, the assembly history and evolution of the Milky Way is still unknown, and our understanding of galaxy formation in the early Universe is currently being upended by the observation of very massive early galaxies and of amazingly quiescent barred and spiral galaxies out to high redshift. These puzzles demand a much-improved theoretical understanding of the evolution of disk galaxies, and in particular of galactic disks.

My work on focuses on building connections between fundamental theory and observations/simulations of galaxies, for instance:

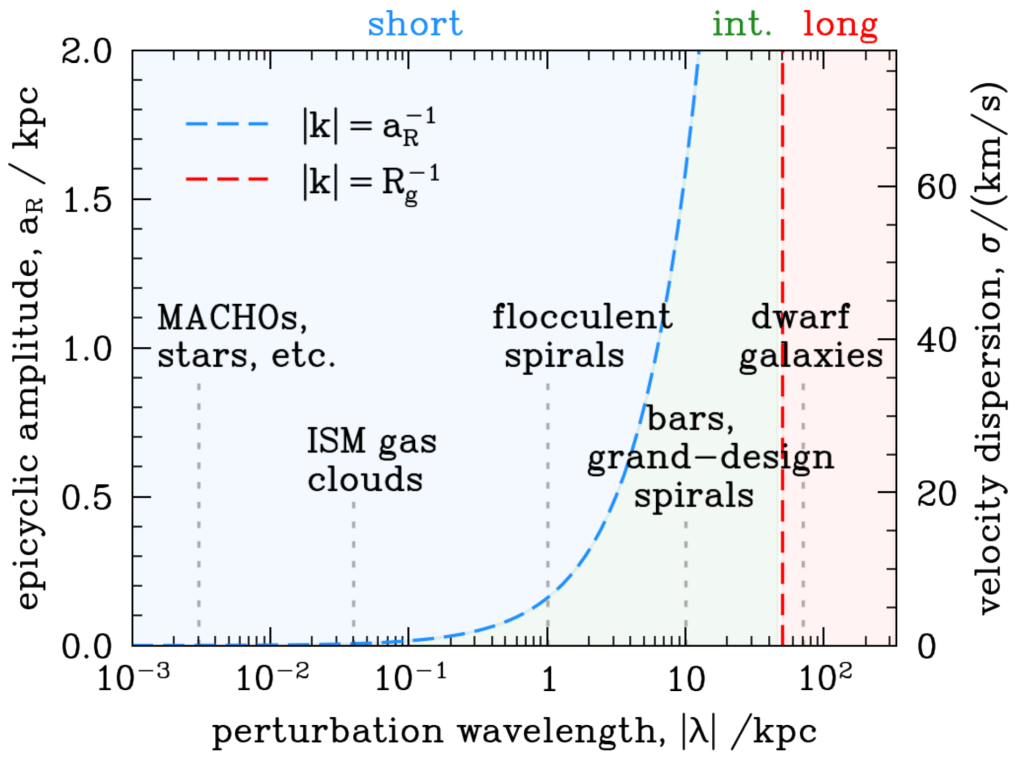

Galactokinetics. A major obstacle that renders the classic kinetic theories of e.g. Lynden-Bell & Kalnajs (1972) largely intractable is that any potential perturbation must be developed in angle-action variables, necessitating a tedious numerical evaluation that provides little insight. In Hamilton et al. (2024) we showed that one can avoid this by splitting potential fluctuations into asymptotic wavelength regimes relative to orbital guiding radius and epicyclic amplitude (similar to plasma gyrokinetics) and then treating separately the dynamics in each regime. The long- and short-wavelength asymptotic regimes join smoothly at intermediate wavelengths. Corrections to this theory are robustly on the order of only a few percent, and e.g. the Lynden-Bell & Kalnajs (1972) torque formula can now be evaluated explicitly.

Saturation of spiral instabilities. Despite decades of argument about the generation of spiral structure in both observed and simulated galaxies, nobody had developed a quantitative theory for spirals’ final saturated amplitudes. In Hamilton (2024) I borrowed from Dewar’s (1973) theory of instability saturation in plasmas to derive a formula for this saturation amplitude, which agrees with scalings found in N-body simulations.

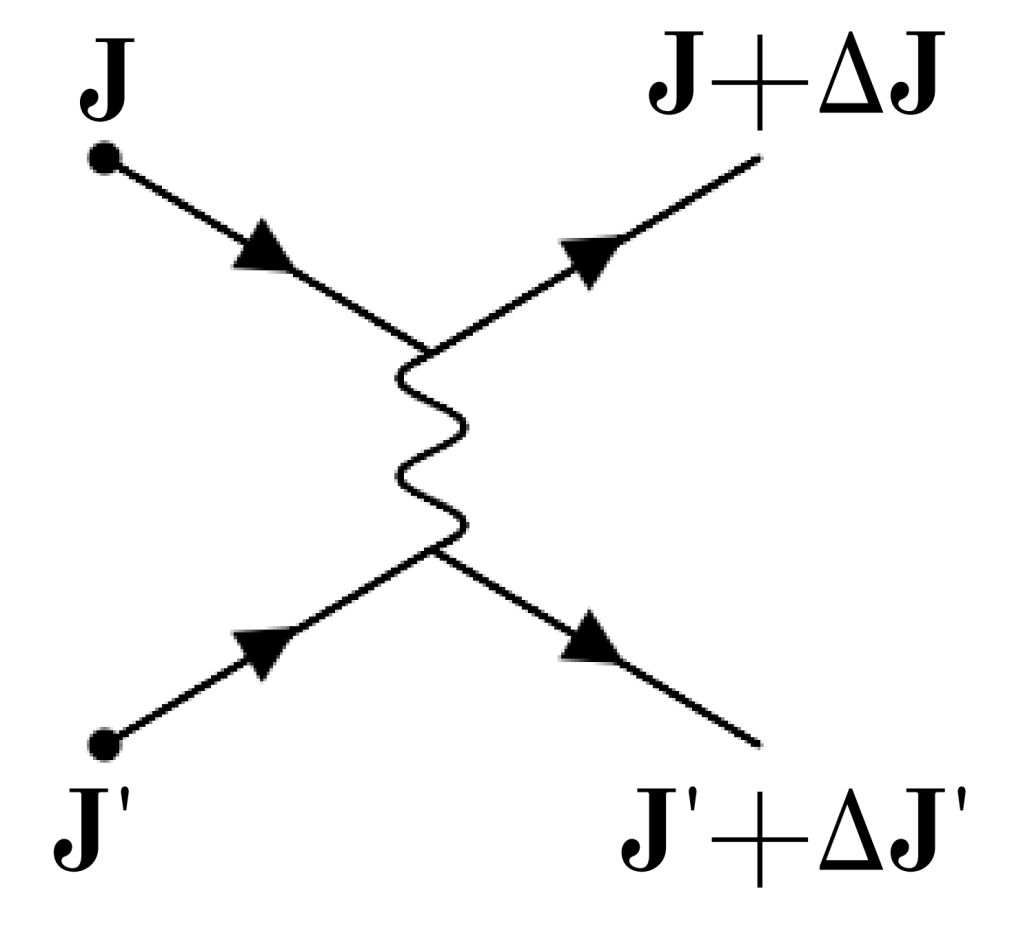

Bar-halo friction. Galactic bars spin down because of resonant interactions between the bar’s rotation and the orbits of dark matter particles. The classic theories of this delicate bar-halo friction process routinely ignored the fact that dark matter particles do not simply orbit in a smooth potential, but also experience random ‘diffusive’ kicks from other passing dark matter clumps, gas clouds, etc. In Hamilton at al. (2023) we quantified the impact of this diffusion on bar-halo friction. The results are important not only for real galaxies but also for analyzing cosmological simulations which purport to simulate `collisionless’ dynamics.

Kinetic Theory of Stellar Systems and Plasmas

For most of the systems I work on, the predominant force is gravity. However, given the similarity between the Newtonian gravitational force and the Coulomb electrical force, many gravitational dynamics problems have analogues in plasma physics. I have co-authored a 66-page tutorial article by invitation of the journal Physics of Plasmas, explaining the links between these two subjects (Hamilton & Fouvry 2024).

Furthermore, I have made a habit of stealing plasma results and applying them to stellar-dynamical problems: for example, I provided the simplest derivation of the Balescu-Lenard collision operator for stellar systems (Hamilton 2021), extended it to systems with weakly damped modes (Hamilton & Heinemann, 2020, 2023), and applied it to globular clusters (Hamilton et al. 2018, Fouvry et al. 2021).

Compact object mergers (LIGO/Virgo sources)

By 2020, LIGO/Virgo was detecting a black hole binary merger almost every week, but the origin of these mergers is still unknown. Given that isolated binary black holes typically have merger times much longer than the age of the Universe, what is causing all these mergers? To resolve this issue we must remember that black hole binaries are not isolated — in other words, we must take account of their environment.

In my graduate work I developed an analytical theory for the evolution of binaries orbiting in arbitrary axisymmetric potentials (Hamilton & Rafikov 2019a, 2019b, 2021, 2024). The key original insight is that by embedding a binary in any such potential we create an effective three-body problem, whereby the potential produces a gravitational tidal torque on the binary that can modify its eccentricity. The formalism I developed brings several classic problems under a simple unified framework: for instance, the hierarchical three-body `Lidov-Kozai’ problem and the problem of Oort comets torqued by the Galactic tide are both just special cases of the same ubiquitous mechanism.

Crucially, the theory applies to black hole binaries orbiting inside globular and nuclear star clusters. It turns out that the tidal torque from a host star cluster is often sufficient to periodically drive a black hole binary’s eccentricity to very high values, leading to a new merger channel (Hamilton & Rafikov 2019c, 2022). This work culminated in Winter-Granic et al. (2024), where we showed that the synergy of (a) cluster-tidal effects and (b) scattering from passing stars leads to a greatly enhanced rate of LIGO/Virgo sources in galactic nuclei.

Wide Stellar Binaries in GAIA

Binary star studies are one of the major successes of GAIA. In particular, ultra-wide stellar binaries (semimajor axes > 1000 AU) have reasserted themselves as key probes of the Galactic environment, of dark matter substructure, and even of our understanding of gravity itself. Wide binaries are also a theorist’s dream: a system which in isolation is exactly solvable, and whose dynamical evolution due to (i) stochastic kicks from passing stars, molecular clouds, etc., and (ii) secular torques from the Galactic tide, can be predicted beautifully with perturbation theory. But we do not understand how these systems form, and there are various observational puzzles surrounding them that remain to be explained.

My research has focused on the highly unusual ‘superthermal’ distribution of wide binary eccentricities (meaning there is an excess of very highly eccentric binaries compared with the naive ‘thermal’ expectation) discovered in GAIA data. With Shaunak Modak, a grad student at Princeton, we proved analytically that neither the Galactic tide nor scattering from passing stars can be responsible for producing this distribution (Hamilton 2022, Modak & Hamilton 2023, Hamilton & Modak 2024). Instead, wide binaries must be born even more eccentric on average than they are observed today. I helped to propose a formation mechanism involving star formation in the turbulent ISM that satisfies this requirement (Xu et al. 2023). These theories also allow for several new predictions, such as the dependence of the eccentricity distribution on binary age and Galactocentric orbit, which can be tested with future data releases.

But the mysteries of wide binaries keep on growing: in Hwang et al. (2022) we showed that twin wide binaries (those where the two stars have very similar masses) are even more eccentric still, perhaps pointing to a circumbinary disk origin.